(Conceptual Overview) A Validity Map for the Gravitational Bohr Model - Reduced-Mass Algebra, Closed-Form Thresholds, and Applicability

How far can a simple story about gravity go before it breaks?

A more conceptual overview of "A Validity Map for the Gravitational Bohr Model"

We often teach physics with simple pictures. They are not perfectly true, but they are good enough to build intuition.

This overview is about one of those pictures, and about where it stops working.

The old picture: atoms as tiny solar systems

In the early days of quantum theory, Niels Bohr pictured an atom a bit like a tiny solar system.

- The nucleus is like the sun.

- Electrons are like planets going around it.

But there is a twist: in the Bohr picture, electrons are not allowed to orbit at just any distance. They can only sit on certain "tracks," like steps on a staircase instead of any point on a smooth ramp. Those allowed tracks are numbered 1, 2, 3, and so on.

That idea turned out to be too simple to be the final word on atoms, but it is still a very useful teaching tool.

Copying that idea over to gravity

In my paper, I take the structure of that Bohr picture and copy it over to gravity.

Instead of an electron and a nucleus, I imagine two masses orbiting each other under ordinary Newtonian gravity (the gravity you learn about with apples and planets).

Then I add one Bohr style rule:

The orbit is not allowed to sit at just any distance. It has to choose from a set of steps or allowed tracks.

So this simple model of gravity has two ingredients:

- Ordinary Newtonian gravity pulling two masses together, and

- A rule that only certain orbit sizes are allowed.

On paper, that is enough to let the math tell you:

- What the first allowed orbit would be (the innermost step), and

- How far apart the energy levels of these orbits would be.

So far, this is just an analogy. It does not mean nature actually makes "gravitational atoms" like this. The point is to use this setup as a clean test case.

The real question: where does this picture make sense?

Once you have a simple model, you can ask a sharp question:

In which situations does this picture still make sense, and in which situations does it clearly fail?

In the paper, I turn that question into two checks that act like guardrails.

1. Size check

The first allowed orbit must lie outside the body that is creating the gravity.

- If the orbit would sit inside the object, then treating the body as a simple point is already wrong.

- Inside real matter, gravity behaves differently, so the simple Bohr style orbit formulas do not apply.

2. Gravity strength check

The orbit must sit in a region where gravity is not too strong and motion is not relativistic.

- If the orbit is too close in, you are in a strong gravity, near black hole type regime.

- There, simple Newtonian gravity plus a Bohr rule is not trustworthy; you need general relativity instead.

These two checks are algebraic conditions. Together, they tell you where this Newton plus Bohr picture could even hope to be self consistent.

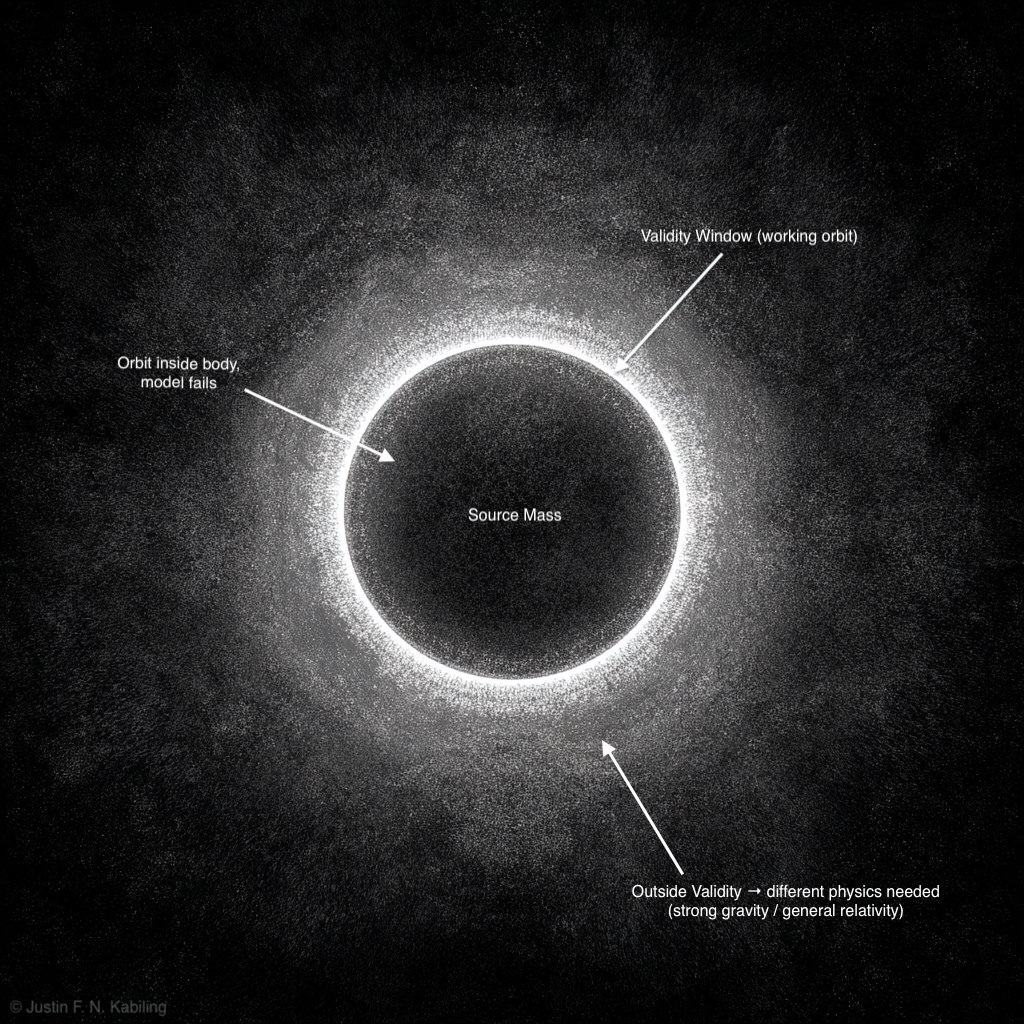

Drawing a "validity map"

The next step is to put both checks on the same plot.

On one axis, you put the mass of the object. On the other axis, you put the size scale (a radius).

Each check draws a boundary on that plot:

- One boundary says: "Inside here, the orbit would be buried inside the body."

- The other says: "Inside here, gravity is too strong; relativity takes over."

Where those two boundaries overlap, you get a narrow band where:

- The orbit sits outside the body, and

- The gravity is still weak enough that Newtonian physics is a decent approximation.

That narrow band is the validity window for this simple gravitational Bohr picture. Outside that window, the model fails in one of the two ways described above.

Most of the map is not a safe zone. Most of it is failure territory.

A concrete example: a neutron and a small mass

To make this less abstract, the paper looks at a specific example: a neutron bound by the gravity of a small mass.

When you run the numbers, the safe zone for this setup only shows up for:

- Very small source masses (in the gram range and below), and

- Microscopic orbit sizes, around the thickness of a human hair or smaller.

Everyday objects and astrophysical objects sit mostly outside this safe window. For them, the first allowed orbit is either inside the body or deep in a strong gravity region where the simple model no longer applies.

So the gravitational Bohr picture is not a general description of the world. It is a toy model that only hangs together in a tiny region of mass and size.

The broader lesson

That is the real point of the paper.

Even a clean, algebraic model has a domain where it works and clear lines where it does not.

- Inside a small window of mass and length scales, the Newton plus Bohr picture of gravity is at least internally consistent.

- Outside that window, you are pushed back to more realistic descriptions of gravity inside matter or to general relativity in strong fields.

The map in the paper is a visual way to show that. It takes a familiar teaching analogy and turns it into a concrete reminder:

Our theories are not magic answers. They are tools with borders. They work in certain regimes, and they must be replaced or extended outside those regimes.

At its core, that is what this work is about: using simple models and algebra not just to get answers, but to draw the boundaries where those models can and cannot be trusted.